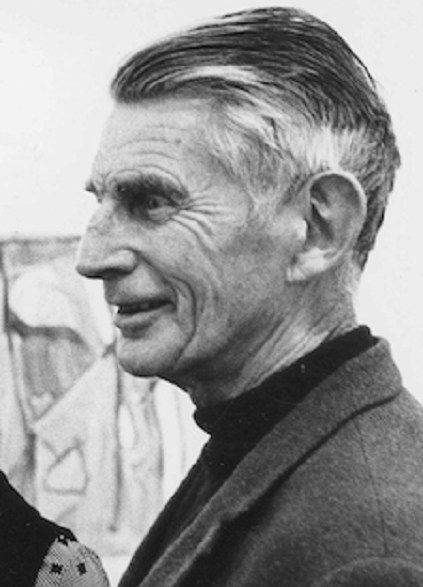

Jack MacGowran was a frail-looking, bird-like man, whose frame belied his power and talent as an actor. You’ll recognize him from The Excorcist, where he played alcoholic director Burke Dennings, or perhaps from Polanski’s Cul-de-Sac, or as Professor Abronsius, in The Fearless Vampire Killers.

If Billie Whitelaw was Samuel Beckett’s favorite actress, then MacGowran was his favored actor. The pair met in the bar of a shabby London hotel, an unlikely start to an “intimate alliance” that saw MacGowran collaborate with Beckett on the definitive versions of Waiting for Godot and Endgame. From this, their partnership led to a further legendary collaboration Beginning to End. As Jordan R. Young noted in his book, The Beckett Actor:

…Jack MacGowran in the Works of Samuel Beckett (aka Beginning to End) [is] one of the most highly-acclaimed one-man shows in the history of theatre, [which] changed forever the public perception of Beckett from a purveyor of gloom and despair, to a writer of wit, humanity and courage. It also brought the actor widespread recognition as Beckett’s foremost interpreter. “The first time I saw Jack, in Endgame… I came away haunted by the impression he made on me,” said Paul Scofield. “I have remained so ever since.”

The production was filmed to celebrate Beckett’s sixtieth birthday:

Beginning to End [which] features the peerless Jack MacGowran in his one-man show, devised with Beckett and recorded for RTÉ Television in 1966. “Jack’s stage presence stays with me more than anything,” said Peter O’Toole. “This frail thing with this enormous power. He walked a tightrope as if it were a three-lane highway.” Martin Esslin, in The Theatre of the Absurd, commented on Beckett’s deep affection for MacGowran: “If ever there was a perfect congruence between a great poet’s imagination and an actor, this was it … Jack MacGowran’s individual quality and life story are an essential ingredient in our understanding of the life and work of one of the outstanding creative minds of our time.”

Rarely seen, and long thought lost, this is a must-see, for it is one of the greatest stage performances ever committed to film.